July 15, 1989

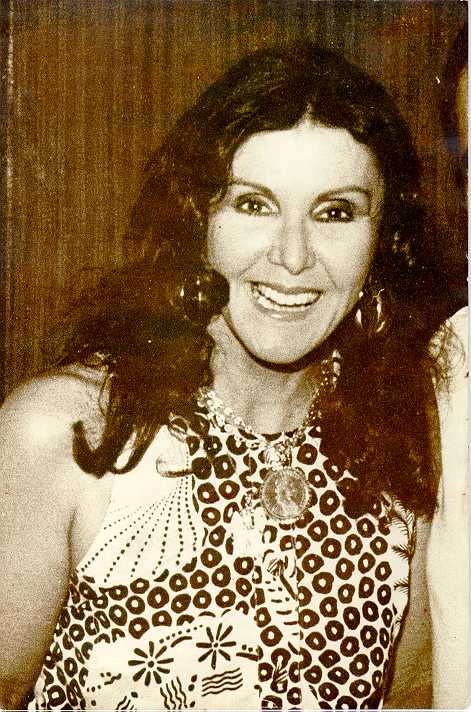

Case: Maria Nilce dos Santos Magalhães

|

Columnist and editor of Jornal da Cidade, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brazil:

April 1, 2001

Clarinha Glock

The police investigation into the death of Maria Nilce dos Santos Magalhães, shot and killed on July 5, 1989 at the age of 48, remains before the 1st Criminal Court in Vitória awaiting an outcome. On April 9, 2001, it was at the stage of formal charges being laid. The case had remained stalled until December 2000, when it was described as an example of impunity in a report by the Chamber of Deputies’ Parliamentary Investigation Committee (CPI).

There are several theories about the motives for Maria Nilce’s murder. Apart from there being rumors implicating a number of people, Maria Nilce had announced she planned to reveal the names of police officers allegedly involved in organized crime and drug trafficking.

Her strong, contradictory character made enemies for her

The resident of the small inland town in Espírito Santo state named Fundão dos Índios, Maria Nilce was engaged to be married when she began to send letters to Djalma Juarez Magalhães, a young reporter the A Tribuna newspaper in Vitória. The two ended up in love. When they married, Maria Nilce was 18 and he was 31. Magalhães took his bride to the newspaper, where she worked as a gossip columnist, until she was fired. He then quit.

The couple had a hard time financially until they decided to launch a new newspaper, Jornal da Cidade. Maria Nilce’s aggressively-style column in the paper made her popular. But she was accused of using her column to extort those who refused to advertise in the paper.

The content of the column affected her children – Milla, 24, Paloma, 21, Fernanda, 27, Djalma Jr. (Juca), 23, and Melissa, 12. "Often, whenever I went to a party I had to find out beforehand if the person giving it was an enemy of my mother," recalls Juca, now 35. And then there were the anonymous telephone calls and crank calls. Juca remembers his mother as being showy, with a difficult character, bossy and politically rightwing. He regarded his father as being very passive, even when he disagreed with her. He was permissive.

Maria Nilce never spoke to her children about death threats. Of the five, Milla, who was with her mother when she was murdered, was the closet to her. As well as exercising together, she worked with her mother organizing events, she ran an office supply store and an art gallery and worked in the newspaper’s subscription department. Milla was not injured in the attack in which her mother was killed because the gun used by one of the assailants failed to fire. After the incident, she could not recall the faces of the murderers, but was surprised when a couple who said they were in the health club that day gave a description of them. According to Milla, the couple said they worked at a nightclub, so she found it difficult to believe that they would be at the health club so early in the morning. She had never seen them at the health club.

Following the murder, Djalma continued receiving threats. Juca was with his father when they noticed an automobile was following them in which appeared to be a bid to scare them. According to Djalma, the car narrowly missed knocking them down and killing them. He reported the incident to the police and asked for protection. He said that an organization calling itself Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq* warned him to leave town.

Milla left Brazil and started a new life abroad. "I think that my mother was murdered because of the hatred of the community in Vitória towards her," she told the IAPA Rapid Response Unit. "She might have all kinds of defects, she might have failed us by not giving us enough attention, but I regard her as the loveliest mother in the world and an extremely strong, talented person with a keen business sense."

She went on to describe her mother as an extroverted, vain, generous (she helped an orphanage and adopted Melissa) and happy person who knew how to tell a joke and liked the arts, singing and dancing. Milla’s husband added that another man, Ibrahim Sued, also a gossip columnist, was crazy about Maria Nilce, who was a member of the jury on television show hosted by the then popular star Chacrinha.

When Maria Nilce died and people started leaving the newspaper, Milla began to write a column – but she soon gave up. Juca says that after his mother’s death the family finances suffered. Without advertisers and with the employees running scared, Jornal da Cidade ceased publication. Traumatized, Djalma spent some time far from his hometown, taking care of his health. The newspaper files and those copies that had not been taken by the police were donated to the local public library.

Milla admitted that a lot pf people did not like Maria Nilce. But nothing, in her view, could explain why she was murdered. "Every human being has the right to life. In my mother’s case, people only see her defects, but that does not justify her death, and that is not the way to get to those really guilty of it," she declared.

There were so many people who were against Maria Nilce that the police investigators initially concentrated on the fights she had engendered, including ones with members of all social classes, to the point that in Vitória relatives and friends believe the theory that a group of enemies had planned her murder.

The fights in general were the result of ill-intentioned and biased comments she wrote in her newspaper column and her exaggerated reactions in her personal relations. Because of her behavior, many colleagues had as little to do with her as possible, while some members of local society felt resentment toward her.

The police looked into a number of these instances, such as hairdresser Francisco Xavier Quintanilha, known as Michel. Maria Nilce often wrote in her column against homosexuals. In an interview with TC Manchete, Michael – well known locally to be gay – said he was not bothered by the criticisms of "some frustrated journalist.". Later that day, Michel said, she went to ask for explanations brandishing a rolling pin and accompanied by her chauffeur carrying a gun.

Something similar happened with merchant Georgina Guimarães da Costa when she tried to collect money Maria Nilce owed her for purchases at her store. Da Costa told police that Maria Nilce in a phone call told her she was willing to pay only part of the debt. She accused the columnist of libeling her in the paper.

Reporter Jorge Luiz dos Santos had a falling out with Maria Nilce and left Jornal da Cidade to go to work at O Diário. Maria Nilce published a photo of him with a cutline asserting that his father was a gunman and his mother a prostitute. She received telephone threats at about that time.

Also known were Maria Nilce’s differences with jewelry store owner Jadyr da Silva Primo, who filed a libel suit against her in connection with what she wrote in the paper in March 1989, four months before her death. One of the stories accused him of being linked to smuggling and illegal bingo and a belonging to group calling itself "Turma do Tambor" (The Drum Gang), drinking buddies who got together and she just made a lot of noise. Maria Nilce said that the stories were meant to be a joke and accused Primo of having provoked "an act of terrorism" during a lunch marking International Women’s Day organized by her, sending two transvestites to the event. Charge and counter-charge of this kind went on. Maria Nilce’s friends recall that one birthday she was sent a cake full of excrement.

Local merchants and business people were the constant target of her mockery and criticism. For example, she called businessman Elias Breda a "coffee shop donkey."

Coffee exporter and consul of Finland in Espírito Santo Gilberto Michelini and his wife, Maria Diva, broke off their friendship with Maria Nilce after she wrote about them in the paper. In one story, she insinuated that their daughter Andrea was illegitimate. The couple were among those suspected of masterminding Maria Nilce’s murder.

Michelini said that his family was nervous and had requested police protection because since May 1989 he had been receiving blackmail threats in letters and phone calls and warning his daughter would be kidnapped. Detective Josino Bragança ruled the Michelinis out as suspects. Later, Detective Cláudio Guerra claimed that the Michelinis had offered a bribe.

At Maria Nilce’s newspaper there were joking references to the clothes women wore and the love trysts among Vitória’s high society. In one story a socialite was accused to wife-swapping, in another the wife of former Governor Elcio Alvarez was called a philanderer.

Maria Nilce welcomed the closure of a casino owned by the speaker of the Legislature, Rep. José Carlos Gratz, and an end to a numbers game popular throughout Brazil. Gratz had worked as a numbers game operator and had gone on to become politically powerful.

It was not unusual for Maria Nilce to fall out with someone who refused to buy advertising in her newspaper – she was in charge of ad sales. Some such people, feeling under pressure, went so far as to issue death threats to her, her husband claimed.

Maria Nilce criticized the "Turma do Tambor" gang more than once. According to her husband, the group included Gratz, gossip columnist Hélio Dória and businessman José Alayr Andreatta.

Maria Nilce had a row with Andreatta’s wife, Sueli. She wrote a story on March 1, 1988, saying that Sueli had nearly knocked her down as she was jogging in a local square.

Andreatta was also suspected of masterminding Maria Nilce’s murder, according to a federal police report. The Rapid Response Unit tried to locate him for an interview, but without success. He had testified that he worked as a real estate agent, but his professional registration had been suspended. He claimed to be a member of the National Information System (SNI), which the SNI chief denied. In 1984, he was jailed for firing a weapon in a bar and injuring a person there. Judge Geraldo Correia Lima interceded on his behalf. He also has charges pending in Rio de Janeiro, where he owns a massage parlor, and in Vitória.

Documentation found at his home shows a close links between him and Correia Lima. In 1986, when he was accused of dealing in stolen vehicles, fraud and unlawful association, Andreatta obtained a habeus corpus signed by Judge Correia Lima and Antônio José Miguel Feu Rosa. Police investigations indicate that Andreatta was believed to have used Correia Lima’s name to rent an airplane used in the getaway of Maria Nilce’s murderers.

The police themselves jeopardized the investigations

The investigations into Maria Nilce’s death were the scene of a curious and confused battle among he police officers assigned to the case, which ended up being transferred to federal jurisdiction at the request of the Public Prosecutor’s Office because of the irregularities. The inquiries implicated in the murder former police officers Elpidio Motta Coelho, Rubens Banhos Pereira, Carlos Roberto Mattos, Antônio Villela, Pedro Jorge de Paula and José Sasso. The Federal Police named Andreatta as suspected of being behind the murder and believed to have used former police officer Romualdo Eustáquio da Luz Faría to hire the hitmen. Rep. Gratz, currently speaker of the Legislative Assembly, was named as Andreatta’s guarantor.

The federal investigation revealed that one of the weapons taken from Andreatta belonged to Correia Lima. According to the official report, Andreatta leased the airplane used in the getaway of the gunmen under the name of Correia Lima. Despite all the evidence, no one has been formally charged.

Before coming up with those names, the inquiries had passed from one police detective to another in Vitória. Detective Josino Bragança, who handled the case initially, was assisted by Detective Cláudio Guerra. Bragança said that he and Guerra received telephoned threats warning them to abandon the case. Several witnesses also said they had received threats.

Shortly after the investigations began in the state, local newspapers reported that the case was practically solved. In a press interview, Guerra and Bragança said that Maria Nilce’s murder involved 12 people and they had used three automobiles. The accused were also responsible for other crimes in the country and a warrant for their arrest was requested. Then the two detectives began to contradict each other, with Bragança accusing Guerra of manipulating the inquiries and leaking information to the press.

One of the incidents that led to Guerra’s departure from the case was a statement by former police officer Valdir Bento de Oliveira on n July 26, 1989, in which he said he knew who had taken part in the murder. On August 8 of the same year he denied everything, saying that the signature on the statement was not his. He said he had been pressured by Guerra and another police officer, Charles Roberto Lisboa.

Guerra was taken off the case. Then Bragança made a new report that eliminate nearly all the initial suspects, maintaining the accusation against only one of them, Carlos Roberto Mattos, who had been identified from a photograph and was at large.

The case went to federal jurisdiction. Police requested a warrant for the arrest of José Sasso and police officer César Narcizo on charges of having carried out the murder. They also implicated in the crime pilot Marcos Egydio da Costa and former Civil Police officer Charles Roberto Lisboa, who initially was part of the team that investigated the case with Detective Cláudio Guerra. Lisboa was accused of having arranged for the automobile for the hitmen and Da Costa of piloting the aircraft that took Sasso to Rio de Janeiro following the murder.

In November, Federal Police Detective Pedro Berwanger formally requested the arrest of Andreatta and Romualdo Eustáquio da Luza Faría, a.k.a. "The Japanese," on charges of masterminding the murder. Da Luz Faría jailed. In December, he and the others being held were released from custody.

The case became news again in 2000 thanks to the Parliamentary Investigation Committee on Drugs. Asked by the IAPA Rapid Response Unit about a Committee report mentioning his name in connection with Maria Nilce’s death, as being a friend of the person accused on masterminding the murder, Rep. Gratz called the report "a piece of used toilet paper." He acknowledged knowing Andreatta but said he was not officially aware of the report. He believed he was being victimized by political opponents. "The Committee is a national farce," Gratz declared. "They brought up the fact that I had been a numbers game operator 12 years ago. I haven’t had anything to do with the game for 10 years now. I did, I would talk." He vehemently denied the existence of organized crime in the state.

Former detective Guerra, now head of the non-governmental environmental organization Clean Up, based in Vitória, is a diving and first-aid instructor and a member of the Vila Sub Dive School. He told the IAPA Rapid Response Unit that he lives now only for his children and grandchildren. As Guerra sees it, the accusations against him are the result of animosities he made during his career as a police officer. He stressed that they were unfounded and added that he had even been accused of receiving contraband weapons when in fact he had merely acquired them as part of an under-cover operation organized by the now-defunct National Information Service (SNI), carried out in the full knowledge of the Brazilian Attorney General’s Office.

Guerra claimed that he took part in the Maria Nilce case investigation because the police chief himself had ordered him to. "I got to the hitman who killed her and probably would have got to the people behind it, but I was prevented from going on with the investigation," he said.

Difficulties in solving the case

—Police corruption and political pressure.

—Fear on the part of witnesses and discrepancies in statements.

—Death threats to witnesses, detectives and others handling the case.

—Irregularities in the investigation: falsified statements, weapons not recovered.

—Officials of the Espírito Santo State Public Prosecutor’s Office assigned to the case gave up because of what they saw an inconclusive inquiry and little evidence. The case was transferred to federal jurisdiction.

Maria Nilce was fearful prior to her death

Maria Nilce’s husband, Djalma, was in Rio de Janeiro on the day of her murder. He had gone there for a medical check-up. He was a diabetic and needed regular visits to his doctor. When he heard from his daughter of the attack on his wife, he rented a car – he was unable to get a flight – and drove to Vitória.

Shortly after Maria Nilce’s death, Djalma began to realize how strange she had been acting in the days before she was killed. He discovered that Maria had recently taken out life insurance. House servants, accustomed to their employer’s outbursts, recalled that at that time she was less aggressive and more relaxed, although just before the day of her death she had seemed worried and avoided going out at night. She did not speak to anyone in the family about her concerns. "I believe someone may have told her something in confidence," her husband said.

Just before her death, Maria Nilce had organized a dinner to which she invited a number of federal police officers. Among them was the superintendent of federal police in Rio de Janeiro, Fábio Calheiros, and his counterpart in Espírito Santo, Oscar Camargo Filho. According to Djalma, Maria said that she was going to announce a "bombshell" that would scandalize the local community and would involve Gratz and Primo,

Nearly one month before the murder there was a robbery at Maria Nilce’s home in which drawers were ransacked and some dollars stolen. The Jornal da Cidade newspaper had previously suffered reprisals for what it had published. On September 14, 1983, a bomb blast ripped through the newsroom. Maria Nilce had had a run-in with Carlos Guilherme Lima, president of the Espírito Santo State Bank (Banestes). He told police that the fight began when he refused to advertise in or subscribe to the newspaper. Then Maria Nilce ran a story on Banestes’ financial results, which he said had been adulterated to make it look as if it had made more money than it had. Lima filed a formal complaint with the Public Prosecutor’s Office, which looked into the matter and Maria Nilce was forced to issue a retraction. In an interview at the time of the bomb blast at the paper, Maria Nilce said the Banestes president was responsible and he in turn accused her of insurance fraud.

In recent times, Djalma and Maria had argued about the future of the newspaper. She wanted to launch a weekly. He preferred to re-invest in the Jornal da Cidade.

Maria Nilce’s explosive temperament caused her to have many enemies, but also faithful friends. Photographer Heitor Bonino de Freitas Pacheco knew her for 20 years and does not remember her ever having any worries. The day before her murder, she had called him to say that she was going to Rio de Janeiro to buy some musical instrument for her son. "she didn’t take seriously the risk she ran over her comments in Jornal da Cidade," Bonino said.

Her way of acting divided her colleagues. Reporter Rogério Medeiros, currently editor of Século magazine, recalls that Maria Nilce was an editorial success, she knew how to make money, but she sometimes went too far and committed errors. "She was an immense danger for the elite of Espírito Santo, which wanted to keep their distance form her," said Medeiros, former president of the Vitória Journalists Union and former city mayor. According to him, it was easy for the elite to say that a judge (Correia Lima) and Andreatta could be behind the murder. "The union never uttered a word and the mainstream press preferred to ignore Maria Nilce’s death because its was an inconvenience," Medeiros said. "That helped the elite could get away with it."

A number of journalists in Vitória kept their mouths shut out of fear. News photographer Romero Mendonça, 47, worked on the Maria Nilce case of the A Tribuna newspaper. He was at the front door of detective Guerra’s home and saw hitman Sasso leave there, not handcuffed, after making a statement. Mendonça photographed Sasso, despite being warned by him not to do so. The following day, a bullet fired by a member of Guerra’s team narrowly missed hitting the photographer as he stood in the patio at police headquarters. The police said it was an accident. Subsequently, Mendonça learned that an unidentified person was hanging around his home and he received anonymous telephoned threats. The photographer, the father of two sons and with 28 years’ experience, quit his job after this case.

Other related crimes

The murder of Maria Nilce is part of a power play in which the pieces are repeated. Criminal attorney Carlos Batista de Freitas, who was handling the defense of José Sasso and César Narciso da Silva, accused of being the hitmen that killed the gossip columnist, disappeared in January 1992. In the inquiries initiated to move the case forward, manipulation of information to prevent discovery of who was behind the murder became evident. There is a common denominator in the names of those directly involved and of intermediaries – the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq.

The detectives initially handling the investigation into lawyer Batista’s disappearance, Júlio César de Oliveira Silva and Ismael Foratini Peixoto de Lima, were taken off the case. Civil Police detective Francisco Vicente Badenes Júnior, who replaced them, called for the two to be charged for their alleged links to organized crime. Badenes maintained that Batista’s disappearance had to do not only with organized crime but with an organization interested in siphoning off public funds and taking control of municipalities and labor unions in Espírito Santo state." The group was dubbed "Mafia Serrana" (Mountain Mob).

Badenes’ report says that collaborating with the group are corrupt public officials in all areas covering up the murder of local union leaders, mayors, criminals, intermediaries, accomplices, witnesses and lawyer Batista. Badenes produced what he said was evidence that the lawyer helped in the escape and defense of those who carried out the murders in order to shield those behind them. Batista’s body was never found, but his car was – completely destroyed by fire.

Although the police inquiry into his disappearance was reopened much earlier, it was not sent to the courts until June 30, 1994, and then at the insistence of Badenes and the Public Prosecutor’s Office.

Batista, a member of the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq organization, had been hired to defend defendants in the June 8, 1990, murder of the mayor of the city of Serra, José Maria Feu Rosa, and his driver, Itagildo de Souza, in Itabela, Bahia state. Following the murder, Deputy Mayor Adalton Martinelli became mayor. The investigations pointed to Martinelli and members of the so-called "Mountain Mob," most of whom belonged to the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq. Police said Alberto Ceolin was among those who ordered Feu Rosa’s murder.

According to statements made to the police, during the mayoral campaign businessmen Antônio Roldi and Adalton Martinelli provided funding for Feu Rosa’s campaign. Members of Feu Rosa’s family confirmed that following his election he refused to accept a kickback in a bid from Roldi’s Tony Tratores company. He also rejected an offer of money from Martinelli to give up the mayorship after he set up a commission to investigate wrongdoing in the local government.

Friends of Batista says that some days before his disappearance he was very nervous and always went around armed with four revolvers. He was having financial difficulties and claimed that Martinelli was not paying him his fees. Batista’s role, apart from defending the accused and arranging for their escape, was to hand over money to the killers’ wives to keep them quiet about Martinelli.

On January 23, 1992, Batista had promised A Gazeta reporter Nelson Gomes that he would give him a dossier on the Feu Rosa case that identified those who carried out the murder and who was behind it. He said it would be a "bombshell" for the Espírito Santo community. On Monday, January 27 he would also hand over the documents to the president of the Espírito Santo Bar Association. He added he would not say any more out of fear for his life.

After Batista’s car was found burned out, the dossier disappeared. The reporter believes that Batista planned to blackmail Feu Rosa’s killers, demanding money to keep quiet. Batista’s mother recalls that he had mentioned Martinelli’s group was also responsible for the death of Sergeant Valdeci Apelheler and another police officer involved in Feu Rosa’s murder.

Charged in Batista’s disappearance and supposed murder were driver João Henrique Filho, former police officer Denerval Gonçalves Pereira, known as Russo, and Geraldo Piedade (who served as Batista’s bodyguard). According to witnesses, the three went with Batista to Martinelli’s home on the day of the crime. Russo was killed some time after at the entrance to the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq. Like him, practically all the others believed to be involved in the murder of Mayor Feu Rosa were themselves killed, except those said to be the masterminds. In winding up the police investigation into the murder, detective Badenes on September 21, 1998, called for the indictment, as masterminds of the crime, of Martinelli, Roldi and Ceolin. Martinelli and Ceolin are now in custody, the latter also on charges of drug trafficking.

Coincidences

1. When he left the mayor’s office in Serra, Martinelli became an adviser to the mayor of Cariacica, Dejair Camata, known as Corporal Camata. Martinelli has earthmoving equipment working for Cariacica city hall and was giving a kickback. Deputy Mayor Jesus Vaz exposed the deal and was the victim of an attempt on his life.

In April 1998, Senate Majority Leader Élcio Alvares called on Espírito Santo State Governor Vitor Buaiz to intercede on behalf of Camata, in jail for arms smuggling. Alvares also is accused of having links to organized crime. Members of the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq acted as Camata’s security guard. Heavily armed, they displayed the group’s logo on their keychains and hats. Camata died in March 2000.

2. Lawyer José Petronetto, who was president of the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq and in charge of the defense of Andreatta (suspected of being behind the murder of Maria Nilce) was the one who informed Batista’s family of his death. Batista’s mother heard Petronetto say he knew about murders that were going to take place in Vitória, but she recognized he did not know about her son’s. Petronetto was district attorney during Martinelli’s term as mayor of Serra. He said he had left the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq before Batista’s disappearance.

3. Former police officer Rubens Banhos confirmed that Batista was murdered by those behind the killing of the Serra mayor because he could incriminate them. Banhos was himself assaulted and killed. He had also been singled out as a suspect in the Maria Nilce murder. His lawyer was Batista.

4. Batista was also the defense attorney of those charged with the murder of French Catholic priest Father Gabriel Maire, a community activist. He was killed in December 1989 in Cariacica. His family is still fighting today for the guilty to be brought to trial for the murder, which has been officially characterized as a fatal robbery. The detective in charge of the case, Pedro Taunnus, is associated with the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq.

5. The Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq is accustomed to handing out meritorious citations. One of those to receive one was Judge Geraldo Correia Lima, in whose name Andreatta, accused in the murder of Maria Nilce, was said to have rented an airplane for those who actually killed her to make their getaway.

6. Elpídio and Areno Benavides, Mayor Feu Rosa’s killers, were also implicated in the Maria Nilce murder. There are documents showing their links to Corporal Camata. Both were themselves murdered.

7. A Federal Police report on Operation Marselha, started in 1990, showed that detectives Júlio César Oliveira Silva (initially in charge of the Batista case), Gilson Lopes dos Santos Filho (who also took part in the investigation into lawyer Batista’s death) and Cláudio Guerra (who helped in the initial investigation in the Maria Nilce case) were involved in car theft, police corruption, the numbers game. drug trafficking, murder and other crimes.

Another name singled out was that of former Civil Police officer Romualdo Eustáquio da Luz Faría, accused of complicity in the Maria Nilce murder. Detective Badenes proved that there was a close link between those involved in Operation Marselha and the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq.

The inquiries into the accuseds’ activities failed to bear fruit. Detective Oliveira Silva, for example, was promoted to special detective. Charges against him were dropped. The Council for the Defense of Civil Rights called on Governor Albuino Azeredo to exonerate the detectives mentioned in Operation Marselha. Romualdo Eustáquio da Luz Faría has yet to answer for his alleged crimes.

8. Members of the press involved with the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq are used to mold public opinion in favor of the criminals.

9. In the Maria Nilce, Batista and Feu Rosa murders there is a consortium of interests. When the intermediaries become a risk, they are eliminated. Hitman José Sasso, jailed for the murder of Maria Nilce, was poisoned on September 18, 1992. Batista’s body has yet to be found.

10. The Maria Nilce case, which involves members of the Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq, remains open.

*What is the Scuderie Detetive Le Coq?

Civil Police detective Francisco Badenes produced a highly-detailed report, with evidence, on the organization called Scuderie Detetive Le Cocq. He said the Scuderie has the appearance of being a philanthropic organization to hide its unlawful activities. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office has called for the organization to be disbanded, but this process is still under way. After becoming aware of fraud committed by the organization and the murder of Batista, Badenes began to receive death threats.

The Scuderie began to be investigated in the 1990s. From 1991 to 1993, Espírito Santo state was notorious in police news due to th4e extermination of children and teenagers in the city of Vitória. The bodies – mainly youths living on the streets who engaged in petty theft who were executed by being shot in the back of the head – were dumped on the street with the aim of creating an impact on the public and a climate of terror in the city. To handle the matter, the state government in 1991 set up a special Administrative Process Commission (CPAE), chaired by a state attorney and one of whose members was Badenes.

The commission came to the conclusion that the death squad was made up of police officers and members of the military belonging to the Scuderie. The inquiries led to its then president, detective Mário Lopes, being charged. Political pressure, however, resulted in the commission being disbanded in August 1994, over protests by the National Human Rights Movement and other similar groups.

A Federal Police report says that the Scuderie had come to wield as much power as the Espírito Santo state government. Its members were involved in the extermination of street children, homicides, car theft and drug trafficking. Impunity is ensured as its members work in various government agencies and can cover up their crimes.

Belonging to the organization are police officers (civil, military and federal), detectives, lawyers, government employees, public prosecutors, judges, politician, businessmen, merchants, journalists and numbers game operators. Badenes established in his report that not all the members are criminals – many only belong to the Scuderie to ensure their personal safety.

Badenes says he has evidence that some Scuderie members are at the service of businessmen and politicians with links to organized crime and of members of the Rural Democratic Union (UDR) in farming areas, and exchange favors with Masonic lodges. The report says that the Scuderie provides funds in mayoral election campaigns and in support of the majority in the Legislative Assembly. In this way it obtains approval of pet projects and jobs in key areas of government. Anyone who does not submit to this control is murdered.

On the other hand, the members of the Scuderie have their safety assured. The Federal Police seized from members smuggled restricted-use weapons, fake police badges, bulletproof vests, hoods and other combat materials.

Founded in Rio de Janeiro in 1994 following the death of detective Milton Le Cocq, the Scuderie adopted as its logo a skull and crossbones with the letters E.M. Although its members are accused of belonging to a death squad (Escuadrão da Morte), they say the initials stand for Motorized Squad (Escuadrão Motorizado). The Scuderie is reported to have representatives in Minas Gerais state and the Brazilian capital, Brasília, as well as in Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo.

The organization was initially made up of police officers ready to avenge the death of detective Le Cocq and root out his killer. In the order to disband the organization issued by the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office in August 1996, it was recalled that Rep. José Guilherme Godinho Ferreira was one of its founders. Known as Sivuca, the congressman was famous for his slogan, "The only good bandit is a dead bandit."

Maria Nilce case taken up by the CPI

In Federal Police reports Espírito Santo is seen as a center of illicit trafficking in drugs, arms and stolen vehicles. Its proximity to Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais states makes it easy for goods and criminals to move about. Investigations have shown that drugs enter the state in boxes dropped from aircraft. The narcotics come from Bolivia, Colombia and Peru and mostly are moved on to Rondônia state for distribution there. The Espírito Santo state capital, Vitória, is regarded as one of the most violent cities in Brazil.

Getting away with murder is nothing new in Espírito Santo. In 1973, nine-year-old Araceli Cabrera Crespo was kidnapped, raped and killed. The perpetrators, identified as members of a leading Vitória family, remain free.

Impunity in the state came to such a dangerous level that residents decided to organize themselves to combat it. In October 1999, in Vitória they founded a Permanent Forum Against Violence and Impunity, better known as "Espírito Santo Reacts." The organization is made up of members of the Roman Catholic church, labor unions, political parties and other sectors of the community. It published a pamphlet with statistics sowing the extent of the violence and suggestions as to how to combat organized crime. One such suggestion was to reinforce the witness and victim protection program. The group aims to bring pressure to bear for crimes to be solved.

"The Forum played an important role as support for the Chamber of Deputies’ Parliamentary Investigation Commission (CPI) on Drug Trafficking," said state congressman Cláudio Verez, who acts as coordinator between the Forum and the Espírito Santo Legislative Assembly’s Human Rights Commission. The CPI’s report issued in December 2000 presents the Maria Nilce murder case as an example of impunity. It gives the names of police officers, politicians and judges it says were involved – reinforcing the conclusions in the Federal Police investigation. Despite all this, the murder remains unpunished.

|